How Many People Do You Meet in a Lifetime?

The average human lifespan today is about 73 years. If you asked anyone how many people a 73-year-old has met throughout their life, you'll usually get an answer in the hundreds or low thousands. "About a thousand" is the most common resting place. It sounds large enough to feel serious, and small enough to feel human.

The number obviously depends on occupation, geography, and temperament. Politicians and activists are outliers so we'll leave them out.

Before counting, the term meeting requires definition, or else we risk going on a wild goose chase. Passing a stranger on the street does not count. Neither does the bank security guard, the pharmacist, nor the market man or woman who sold you vegetables once.

Meeting someone, for our purposes, means repeated exposure over time: enough to recognize them, enough to place them in context, enough that influence is possible (both ways). For me the threshold is crossed when I can remember their surname and given name (and they can remember mine), know how their voice sounds and have engaged in some sort of conversation or group activity with them. Pretty low bar.

Strangers can still alter a life meaningfully. A violent stranger who breaks into your home and kills your family has more influence than a hundred friends combined. It's a single interaction that changes life forever. But that is far from common. So we count persistent encounters

UN data shows that roughly 45% of the world's population lives in cities, 36% in towns or suburban areas, and 19% in low-density rural areas. This suggests that globally, the vast majority of people live in towns or cities.

In towns and cities, social circles are constrained by institutional overlap and intersection of routines in neighborhoods, workplaces, schools, and family networks. And that's the logic we'll use to check whether the figure 1000 was an accurate guess.

By age 12, most have met a surprisingly large number of people. Immediate and extended family typically accounts for 20 to 30 people. Primary school introduces roughly 30 classmates per year over six years, with partial turnover, yielding about 100 distinct peers. Add teachers, neighbors, parents of friends, and community figures, and the number approaches 200. Conservatively, preteen years contribute 180 to 200 persistent encounters. I went to a particularly small primary school and these numbers don't speak to my personal experience, but hey, I'm writing with the average man in mind.

Secondary school cohorts are larger, social circles widen, and friends of friends become relevant. A typical secondary school might expose a student to 200 peers across several years. If we add extracurriculars, religious groups, and neighborhood expansion, we can add more 100 to 150 encounters. By age 18, the running total is around 450 to 550.

Early adulthood is the most socially dense phase of life. University, vocational training, or early employment introduces hundreds of age-matched peers encountered. A single cohort can easily contain 300 people, of whom perhaps half are encountered persistently. Add roommates, romantic partners' networks, and secondary spillover, and early adulthood contributes 400 to 500 encounters. By the mid-twenties, the total sits around 900 to 1,000.

Things generally cool down from here.

From roughly age 25 onward, you're past the peak of friend making. Workplaces stabilize. Social circles repeat. You still meet new people, but slowly. Assuming, generously, 2 to 3 new persistent encounters per month including coworkers, collaborators, clients, neighbors, that is about 30 per year. Also the effect of the individual's temperament matters a lot here . Some people are just not outgoing, and even 30 per year feels optimistic. But let's keep it.

Over 35 years of working adulthood, this yields 1,050 encounters. If you consider moves, job changes, and the simple fact that many professional relationships are really just polite corridor greetings, that leaves 600 to 650 meaningful encounters. Late adulthood and retirement contracts the number of new people you meet greatly but does not entirely eliminate it. Healthcare providers, community members, extended family growth, and neighborhood turnover add perhaps 100 to 150 more.

Add the stages together and the lifetime total settles between 1,600 and 2,000 people.

That is the average truth.

So what does this number actually mean for the friendships we can have in a lifetime?

Jeffrey Hall's work on friendship formation provides a rare quantitative anchor. In his paper, turning a stranger into a casual friend requires roughly 50 hours of interaction. Turning them into a simple friend takes around 90 hours. Turning them into a close friend requires approximately 200 hours.

Across 73 years, the total social time budget—the time spent on making friends is not uniformly distributed. Infancy and early childhood contribute essentially nothing to discretionary friendship formation. Middle childhood through adolescence (roughly 6 to 18 years) offers perhaps 1.5 hours per day over 12 years (~6,600 hours). Early adulthood peaks at 0.75 hours per day over 7 years (~1,900 hours). Prime adulthood sustains about 0.5 to 0.75 hours per day over 30 years (~5,500 to 8,200 hours). Late adulthood declines to 0.5 hours per day over 18 years (~3,300 hours). The lifetime total is roughly 17,300 to 20,000 hours.

Divide this by the 1,600 to 2,000 people you meet, and each person receives an average of 9 to 13 hours across your entire life. But time is not distributed evenly. Most people get far less than the average. A few get vastly more. If you allocate 90 hours each to reach simple friendship, you can sustain a maximum of roughly 190 to 220 simple friends over a lifetime (17,300 to 20,000 ÷ 90). More realistically, accounting for natural drift, falling out, and relocation and the fact that mere minutes are spent socializing with the vast majority of the thousands you meet, you retain 20 to 40 at the simple friend level. At 200 hours per close friend, the theoretical maximum is 86 to 100 (17,300 to 20,000 ÷ 200). In practice, you sustain 5 to 10 close friends. Best friends, requiring sustained investment over decades, number 1 to 3.

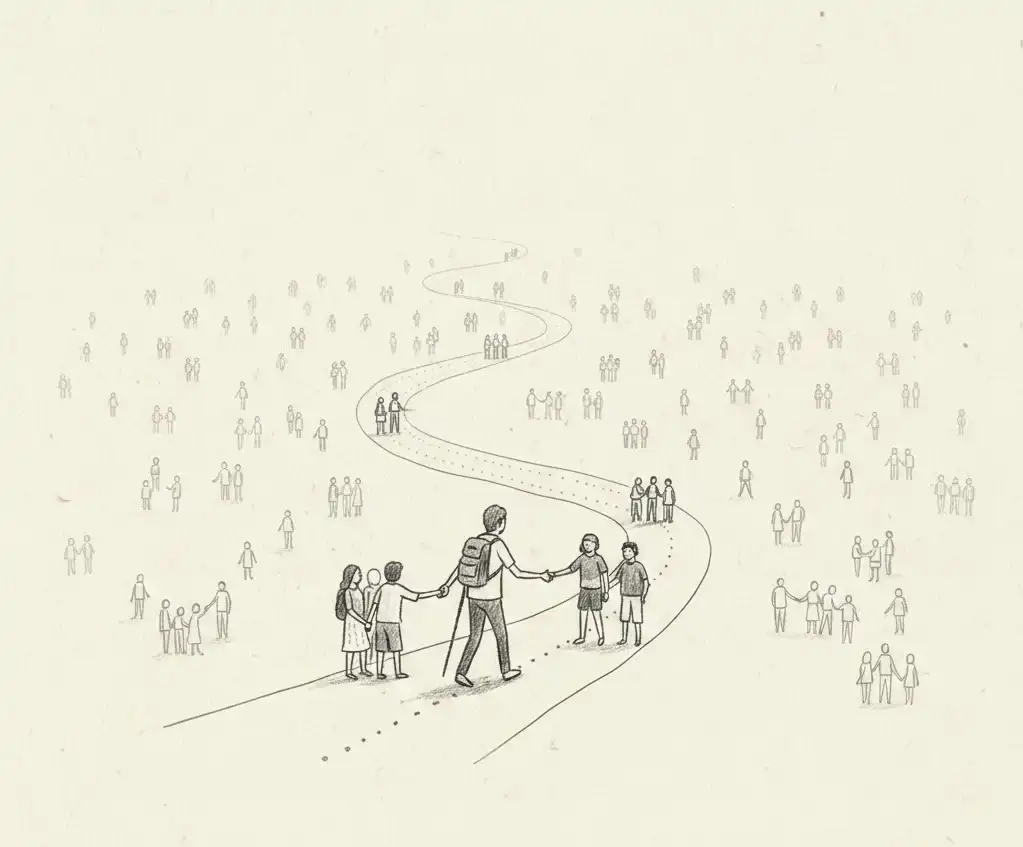

Phew! Welcome back from that! But the lengthy count was worth the effort because opportunity moves through people. Jobs, ideas, capital, exits, warnings, leverage. None of these appear spontaneously. If no one in your encounter set has crossed a certain economic, institutional, or intellectual threshold, that threshold is unlikely to enter your future.

The internet could have helped. It changes where you meet people and which kind. However most digital encounters never amount to much. They remain lightweight, low-commitment, and interchangeable. Occasionally online, someone impactful enters your life who would never have appeared otherwise. But these are rare.

So, in a lifetime, you will meet only a few thousand people yet you will deeply know (with mutual fondness) only a few. And the vast majority of what you become will be shaped by whoever circumstance placed within reach. May God help us with the quality of those few then!